I decided to pick up The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams because I know it's a favorite novel among nerds. From nerds in high school to nerds on He-Man.org, it is a well-liked book.

My review? Mehhhhh. Recommended? Mehhhh. But maybe my expectations were set too high. From the back jacket: "As parody, it's marvelous: it contains just about every science fiction cliché you can think of. As humor, it's, well, hysterical"—The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Yes, it is a well-written parody. From the two-headed alien President, to who actually controls Earth, to the Improbability Drive, it pokes fun at those things that make sci-fi identifiable. But I didn't think it was hysterical. I thought it was "just there..."

I don't want to trash it, because it has a good premise and some great characters. Some good points are made outside of "haha, look at this sci-fi cliché turned on its head."

For example, Zaphod Beeblebrox, President of the Imperial Galactic Government, exists as a leader solely to distract his constituents from what is really happening in the galaxy (p. 39). He reminds me of our current US president, except ours doesn't have two heads. But the Government loves to exploit a situation (*cough*9/11*cough* Terrorists/Ahhh!) to distract us (War? What war?). This was a wonderful observation on Adams' part about the way governments work. They make us fear something that has nothing to do with anything.

Decent book, but I think I expected to much. I liked it, but didn't find it hysterical, "extremely funny" (Washington Post) or "reminiscent of Vonnegut" (Chicago Tribune).

There is funnier Sci-Fi out there: it's called the history of Xenu (from Wiki).

Next up: Speaking of being reminiscent of Vonnegut, Galapagos. Don't expect this review for two weeks, though.

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

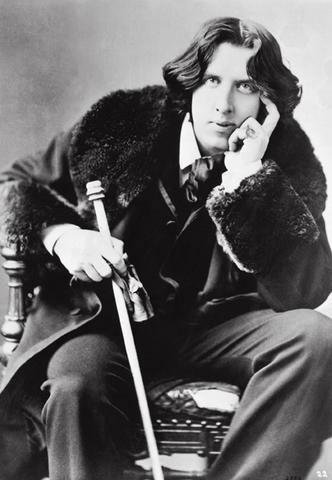

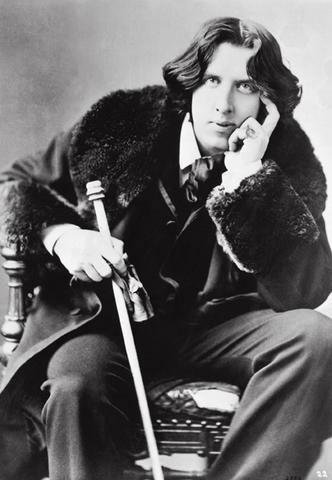

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

Several years ago, near the end of my English major classes, I read "The Importance of Being Earnest" by Oscar Wilde. HILARIOUS. I then said to myself, "I must read more of this Oscar Wilde. He is funny, smart, and of course flaming."

I have long admired Wilde for his writing and his fashion, so it made sense to pick up The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde for cheap.

This week I read his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. It is a must-read for any person, as you will suddenly "get" all references made to Dorian Gray (look, I just came across one yesterday in my daily blog-reading), and you will quickly learn that Wilde writes in aphorisms. Seriously -- everything the guy puts down on paper is a punchy universal truth. You know someone is a master if they do something better than Shakespeare...

So, Dorian Gray... Glad I read it. Would I recommend it? Not necessarily. It was written in Victorian England, and definitely reflects the time period. All of the description gets boring (typical of the Gothic novel), and sometimes Wilde's wit is just exhausting. But, if you can get past those minor quibbles, please read it!

The protagonist is Dorian Gray, a fashionable, beautiful, rich young man whose friend, Basil Hallward, paints a magnificent portrait of him. Dorian wishes he could remain as gorgeous as that portrait forever... The novel follows his life primarily, including his near-marriage, his addiction, and his, umm, bad decisions...

Within pages of reading I scribbled a question on my bookmark—"is every line an aphorism?" (if it isn't a universal truth, it is still a witty epigram). The answer is "Not quite, but close." The character of Lord Henry is the greatest provider of these; he is like the best friend who influences you to smoke pot, drink cheap beer, or skip class. You know you will have a good time with him, but your other friends warn you to stay away... Here are just a few I underlined while reading:

And so these are some of the lessons imparted to impressionable, young and beautiful Dorian Gray. You know, this is why Lindsay Lohan had so many problems. She had too many people like Lord Henry around!

Part of the reason I decided to pick this novel up is because I'd lived by the preface alone (see my blog about blogging). I liked to pick it apart and admire the language, using it support any argument I had (most often with myself) about aesthetics. Wilde was inconsistent, as I explained in that ol' blog of mine. So am I. So is literature.

Is Dorian Gray didactic? Is it a rumination on our obsession with youth and beauty? Is it simply a well-written book? You know, I could expound on these and other questions for ages. But, I did that with my review of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, so I figure I'll give that a rest.

My recommendation:

Read this novel, especially if you are one of those people who likes to read "the classics." This one is considered a classic for good reasons:

Did you know "Dorian Gray had been poisoned by a book?" (chapter 11). Is this possible?

Why does art exist? Some say "it's an outlet" or "it's to show our true selves." Do you think a work of art can come alive? Or somehow retain the essence of its subject?

Oh, and be careful what you wish for. That is all.

Next up: The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams. (Let's see if I can handle a sci-fi book that makes fun of sci-fi).

I have long admired Wilde for his writing and his fashion, so it made sense to pick up The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde for cheap.

This week I read his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. It is a must-read for any person, as you will suddenly "get" all references made to Dorian Gray (look, I just came across one yesterday in my daily blog-reading), and you will quickly learn that Wilde writes in aphorisms. Seriously -- everything the guy puts down on paper is a punchy universal truth. You know someone is a master if they do something better than Shakespeare...

So, Dorian Gray... Glad I read it. Would I recommend it? Not necessarily. It was written in Victorian England, and definitely reflects the time period. All of the description gets boring (typical of the Gothic novel), and sometimes Wilde's wit is just exhausting. But, if you can get past those minor quibbles, please read it!

The protagonist is Dorian Gray, a fashionable, beautiful, rich young man whose friend, Basil Hallward, paints a magnificent portrait of him. Dorian wishes he could remain as gorgeous as that portrait forever... The novel follows his life primarily, including his near-marriage, his addiction, and his, umm, bad decisions...

Within pages of reading I scribbled a question on my bookmark—"is every line an aphorism?" (if it isn't a universal truth, it is still a witty epigram). The answer is "Not quite, but close." The character of Lord Henry is the greatest provider of these; he is like the best friend who influences you to smoke pot, drink cheap beer, or skip class. You know you will have a good time with him, but your other friends warn you to stay away... Here are just a few I underlined while reading:

- ...there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about (chapter 1).

- And Beauty is a form of genius—is higher, indeed, than Genius, as it needs no explanation (2).

- All influence is immoral... because to influence a person is to give him one's own soul (2).

- There is absolutely nothing in the world but youth! (2)

- To get back one's youth, one has merely to repeat one's follies (3).

- Nowadays people know the price of everything, and the value of nothing (4).

- Faithfulness is to the emotional life what consistency is to the life of the intellect—simply a confession of failures (4).

- Yes, we are overcharged for everything nowadays. I should fancy that the real tragedy of the poor is that they can afford nothing but self-denial (6).

And so these are some of the lessons imparted to impressionable, young and beautiful Dorian Gray. You know, this is why Lindsay Lohan had so many problems. She had too many people like Lord Henry around!

Part of the reason I decided to pick this novel up is because I'd lived by the preface alone (see my blog about blogging). I liked to pick it apart and admire the language, using it support any argument I had (most often with myself) about aesthetics. Wilde was inconsistent, as I explained in that ol' blog of mine. So am I. So is literature.

Is Dorian Gray didactic? Is it a rumination on our obsession with youth and beauty? Is it simply a well-written book? You know, I could expound on these and other questions for ages. But, I did that with my review of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, so I figure I'll give that a rest.

My recommendation:

Read this novel, especially if you are one of those people who likes to read "the classics." This one is considered a classic for good reasons:

Did you know "Dorian Gray had been poisoned by a book?" (chapter 11). Is this possible?

Why does art exist? Some say "it's an outlet" or "it's to show our true selves." Do you think a work of art can come alive? Or somehow retain the essence of its subject?

Oh, and be careful what you wish for. That is all.

Next up: The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams. (Let's see if I can handle a sci-fi book that makes fun of sci-fi).

Monday, July 7, 2008

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick

Yesterday I finished reading Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick. This book is well-known as the basis for Blade Runner, which is one of my favorite films.

Understandably, then, I can't help but discuss the movie while discussing the novel. First: if you disliked the movie, you should still read the book. They are quite different. Conversely, if you read the book and don't like it, still give Blade Runner a chance.

If you want to be challenged, read the book after watching the movie or before. I just recommend that you don't "read up" on the book before tackling it. There are so many articles out there that give too much away (e.g. Wikipedia's). I will strive to give little away.

So—the novel. We start out by learning of Deckard, the bounty hunter. He stands to make a thousand bucks for retiring (killing) an android (known in the film as a replicant). We create these androids to be servants on our colonies; they are in our image, and to 99.9% of the population, appear to be human. Deckard is out to retire them because they killed their masters in order to flee servitude and live on Earth.

The year is 2021 (in earlier editions of the novel, it was an earlier year. They changed this for some reason), and following World War Terminus, there are few inhabitants of Earth. The people who remain are obstinate (think of Harry Truman— not the President—who refused to leave Mt. St. Helens as it erupted) or "special". We've destroyed earth, leaving it a radioactive wasteland with few habitable locations. Gee, this sounds like it could really happen...

Most Earthlings have fled to colonies such as Mars. You're crazy to remain on Earth. If you move to a colony, you get your very own android slave! However, copulation with an android is illegal, so don't think about moving to Mars so you can get some hot robot ass. "Specials", also known as chickenheads, are humans considered too inferior to leave Earth — we don't want them reproducing or mucking up our new colonies. These specials usually have damaged genes from waste of the war, often resulting in mental retardation.

To keep ourselves company, we buy pets. However, real animals are hard to come by, not to mention expensive. Thus, most of us have electric animals—hence the title. There are a few key items all people have, including machines that manipulate our emotions and a T.V. that gets one government channel. We read about how barren our planet is—but very little about the physical setting (so when you watch Blade Runner, you are seeing the imagination of the screenwriters, director, etc, not Dick's).

Dick is focused more on character development and philosophical themes. There are many characters in the novel who don't appear in the film. Most notably is that of Phil Resch, a fellow bounty hunter. It is through this character that we, and Deckard, try to understand what the difference between a human and android (andy) is. Tests performed on potential andys try to reveal a lack of empathy. Empathy is a trait that only humans possess. So, is that what makes an andy inferior? Resch complicates this, as he is accused of being an android, which is something he had never considered. If he does test out as an android, he believes that suicide is the only resolution.

Androids are implanted with false memories, so if they are never told they are androids—if they are never constantly reminded—they could potentially believe themselves human. If they have emotions, memories and original thoughts, how are they not human? It's a delay in empathy. They feel for humans and animals, as they are taught to. But it is all calculated.

Great sci-fi writers layered theme upon theme in each novel. Because it's sci-fi, it's easier for the masses to consider: what it means to be human, what it means to be a slave, how we are destroying our planet, what the future holds, etc. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? we have to consider all of these things. Why are andys considered so inferior? We created them; they are organic, unlike our electric pets. So, is it really ok to hunt them down and murder them? What about Luba Luft, an extremely talented Opera singer who happens to be an andy? Deckard wonders, "how can a talent like that be a liability to our society?" (120). Why is it OK to kill them? Are humans really separated by this magic trait—empathy—if we have no problem killing androids?

This theme manifests itself, for real, in the United States when we consider that anything but heterosexual marriage is banned in many states. It wasn't too long ago that public schools were racially segregated. Standing in any retail location, walking down the street, or sitting in a classroom you feel the same kind of hate and superiority towards Mexicans, whether they are illegal immigrants or not. Why is it OK to blindly hate? In the novel, our cover is, that the androids killed their masters to escape. But why was it ok for them to be enslaved in the first place? We are the ones who gave them the capability to dream and feel, yet we don't allow them to do much more than till our fields or clean our houses (wow, this theme is relevant, yet again).

I need to stop, or I'll give away the whole book and write ten pages no one will read.

My recommendation is a Yes, read this book. Sorry if I got too political, but damnit, that's the point of sci-fi.

KK

Next up: The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

Understandably, then, I can't help but discuss the movie while discussing the novel. First: if you disliked the movie, you should still read the book. They are quite different. Conversely, if you read the book and don't like it, still give Blade Runner a chance.

If you want to be challenged, read the book after watching the movie or before. I just recommend that you don't "read up" on the book before tackling it. There are so many articles out there that give too much away (e.g. Wikipedia's). I will strive to give little away.

So—the novel. We start out by learning of Deckard, the bounty hunter. He stands to make a thousand bucks for retiring (killing) an android (known in the film as a replicant). We create these androids to be servants on our colonies; they are in our image, and to 99.9% of the population, appear to be human. Deckard is out to retire them because they killed their masters in order to flee servitude and live on Earth.

The year is 2021 (in earlier editions of the novel, it was an earlier year. They changed this for some reason), and following World War Terminus, there are few inhabitants of Earth. The people who remain are obstinate (think of Harry Truman— not the President—who refused to leave Mt. St. Helens as it erupted) or "special". We've destroyed earth, leaving it a radioactive wasteland with few habitable locations. Gee, this sounds like it could really happen...

Most Earthlings have fled to colonies such as Mars. You're crazy to remain on Earth. If you move to a colony, you get your very own android slave! However, copulation with an android is illegal, so don't think about moving to Mars so you can get some hot robot ass. "Specials", also known as chickenheads, are humans considered too inferior to leave Earth — we don't want them reproducing or mucking up our new colonies. These specials usually have damaged genes from waste of the war, often resulting in mental retardation.

To keep ourselves company, we buy pets. However, real animals are hard to come by, not to mention expensive. Thus, most of us have electric animals—hence the title. There are a few key items all people have, including machines that manipulate our emotions and a T.V. that gets one government channel. We read about how barren our planet is—but very little about the physical setting (so when you watch Blade Runner, you are seeing the imagination of the screenwriters, director, etc, not Dick's).

Dick is focused more on character development and philosophical themes. There are many characters in the novel who don't appear in the film. Most notably is that of Phil Resch, a fellow bounty hunter. It is through this character that we, and Deckard, try to understand what the difference between a human and android (andy) is. Tests performed on potential andys try to reveal a lack of empathy. Empathy is a trait that only humans possess. So, is that what makes an andy inferior? Resch complicates this, as he is accused of being an android, which is something he had never considered. If he does test out as an android, he believes that suicide is the only resolution.

Androids are implanted with false memories, so if they are never told they are androids—if they are never constantly reminded—they could potentially believe themselves human. If they have emotions, memories and original thoughts, how are they not human? It's a delay in empathy. They feel for humans and animals, as they are taught to. But it is all calculated.

Great sci-fi writers layered theme upon theme in each novel. Because it's sci-fi, it's easier for the masses to consider: what it means to be human, what it means to be a slave, how we are destroying our planet, what the future holds, etc. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? we have to consider all of these things. Why are andys considered so inferior? We created them; they are organic, unlike our electric pets. So, is it really ok to hunt them down and murder them? What about Luba Luft, an extremely talented Opera singer who happens to be an andy? Deckard wonders, "how can a talent like that be a liability to our society?" (120). Why is it OK to kill them? Are humans really separated by this magic trait—empathy—if we have no problem killing androids?

This theme manifests itself, for real, in the United States when we consider that anything but heterosexual marriage is banned in many states. It wasn't too long ago that public schools were racially segregated. Standing in any retail location, walking down the street, or sitting in a classroom you feel the same kind of hate and superiority towards Mexicans, whether they are illegal immigrants or not. Why is it OK to blindly hate? In the novel, our cover is, that the androids killed their masters to escape. But why was it ok for them to be enslaved in the first place? We are the ones who gave them the capability to dream and feel, yet we don't allow them to do much more than till our fields or clean our houses (wow, this theme is relevant, yet again).

I need to stop, or I'll give away the whole book and write ten pages no one will read.

My recommendation is a Yes, read this book. Sorry if I got too political, but damnit, that's the point of sci-fi.

KK

Next up: The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

I've heard the name David Sedaris thrown around -- I've heard he writes some funny books. I also knew he was the brother of Amy Sedaris, who is responsible for the creation of my MySpace Hero, Jerri Blank of Strangers with Candy.

Hearing one is funny and being related to Amy Sedaris are certainly qualifications enough for me to pick up a book. So, I borrowed Me Talk Pretty One Day from Nate and read it this last week.

And yes, it was funny. It is an anecdotal book, with each chapter showing us a little from David Sedaris's life. They are amusing, short chapters; you don't have to read the whole book to get the picture. This would be something to keep on your shelf for a little pick-me-up -- just read a chapter and you'll feel better.

Sedaris writes mostly of his childhood speech impediment, teaching a writing class and moving to Paris to learn French. My favorite part of the book was definitely the American in Paris part. It was a hilarious jaunt through foreigners' conceptions of Americans, and of Americans' conceptions of foreigners. I feel I learned a lot about France, too, which was a bonus. Did you know that rather than having a rabbit deliver chocolate on Easter, the French have a bell do the dirty work? Seriously. Sedaris claims that is "fucked up" (180).

A great vignette involves Sedaris using public transportation, where he meets two Fellow Americans. However, because he doesn't say anything to him, and, well, most Americans are idiots, they assume he's a French pickpocket.

It's funny. I definitely recommend reading it if you want to laugh.

Next up: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

I've heard the name David Sedaris thrown around -- I've heard he writes some funny books. I also knew he was the brother of Amy Sedaris, who is responsible for the creation of my MySpace Hero, Jerri Blank of Strangers with Candy.

Hearing one is funny and being related to Amy Sedaris are certainly qualifications enough for me to pick up a book. So, I borrowed Me Talk Pretty One Day from Nate and read it this last week.

And yes, it was funny. It is an anecdotal book, with each chapter showing us a little from David Sedaris's life. They are amusing, short chapters; you don't have to read the whole book to get the picture. This would be something to keep on your shelf for a little pick-me-up -- just read a chapter and you'll feel better.

Sedaris writes mostly of his childhood speech impediment, teaching a writing class and moving to Paris to learn French. My favorite part of the book was definitely the American in Paris part. It was a hilarious jaunt through foreigners' conceptions of Americans, and of Americans' conceptions of foreigners. I feel I learned a lot about France, too, which was a bonus. Did you know that rather than having a rabbit deliver chocolate on Easter, the French have a bell do the dirty work? Seriously. Sedaris claims that is "fucked up" (180).

A great vignette involves Sedaris using public transportation, where he meets two Fellow Americans. However, because he doesn't say anything to him, and, well, most Americans are idiots, they assume he's a French pickpocket.

It's a common mistake for vacationing Americans to assume that everyone around them is French and therefore speaks no English whatsoever. These two didn't seem like exceptionally mean people. Back home they probably would have had the decency to whisper, but here they felt free to say whatever they wanted, face-to-face and in a normal tone of voice. It was the same way someone might talk in front of a building or a painting they found particularly unpleasant. An experienced traveler could have told by looking at my shoes that I wasn't French. And even if I were French, it's not as if English is some mysterious tribal dialect spoken only by anthropologists and a small population of cannibals. They happen to teach English in schools all over the world. There are no eligibility requirements. Anyone can learn it. Even people who reportedly smell bad despite the fact that they've just taken a bath and are wearing clean clothes.

Because they had used the tiresome word froggy and had complained about my odor, I was now licensed to hate this couple as much as I wanted. This made me happy, as I'd wanted to hate them from the moment I'd entered the subway car and seen them hugging the pole. Unleashed by their insults, I was now free to criticize Martin's clothing: the pleated denim shorts, the baseball cap, the T-shirt advertising a San Diego pizza restaurant. Sunglasses hung from his neck on a fluorescent cable, and the couple's bright new his-and-her sneakers suggested that they might be headed somewhere dressy for dinner (221-222).

It's funny. I definitely recommend reading it if you want to laugh.

Next up: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)